There are white lace curtains in every window. The gossamer fabric filtered the morning sun and broke up the severity of the inlaid wood panels that line the large room where breakfast was served this morning. We sat around a beautiful old walnut dining table that was genteelly set with china, perfectly placed. What once was an antebellum ball room, now serves as an oversized dining room, part of a converted mansion built in 1856. Every morning at 8:30am, a very civilized time, the hotel guests are served a complimentary three course breakfast. First a bowl of fruit, then quiche, grits and a muffin. A small pastry compliments the light fare as a the closer.

Seated at the table are a couple from Oregon who own a bed and breakfast, two young men from Switzerland here to tour the south, and a fellow traveler who’s done a lot of ‘walk about.’ Quite literally. He is from Alabama and has that slow drawl that the famous Mississippi historian, Shelby Foote, used to great effect in Ken Burns' famous civil war documentary. He sits at the head of the table; the opposing seat at the other end of the table remains empty. He is holding court. He explains to us that the reason that the ceilings are so tall in the dining room is to minimize the effects of the heat that collects in the room on its occupants, especially those dancing. The tall ceiling served as a design element throughout the south before the widespread adoption of air conditioning. It is not hard to imagine the belle of the ball standing there with her dance card waiting for a dashing confederate officer to make an offer.

Mr. Alabama has walked the entire Appalachian Trail. It took him a few months. He has also done something similar in the UK, and something like it the Alps. I’d say he is about 65. He compliments the young Swiss men on choosing to see the south rather than traveling to Los Angeles or New York City. One of the men tells him that they did that on their last trip to the states. Mr. Alabama does not skip a beat. He tells the young men where to travel on their next sojourn to the United States. I chime in that when they think they have seen it all – come on back again – “this time come to Vermont.” That gets a laugh from the couple from Oregon and the young men, too.

Mr. Alabama changes the topic. He begins to expound about the late disagreement between the north and the south over Vicksburg. He asserts that it was not a battle won by the north, but it was a siege lost by the south. He points out that by calling it the ‘Battle of Vicksburg’ one implies that the Confederate States were defeated on the field. They were not. He is right. They were reduced by hunger to surrender. The ‘Siege of Vicksburg,’ he argues with evident pride, came about because the Union Army could not vanquish the troops defending her. So – Grant starved them out. (I did not mention that the southern leadership betrayed the defending Confederate army by declining to send a reliving force to Vicksburg, precisely because they feared defeat in the field at the hands of Grant’s army.) At this point the woman who owns the mansion, and who was helping her staff to serve the breakfast, interjects that she makes frequent evening lectures to organized tour groups about ‘The Siege of Vicksburg.’ She said that 70,000 Union troops surrounded the garrison of Vicksburg, while a contingent of only 30,000 rebels defended the city and its fortifications. Of course, she didn’t use the term ‘rebel’, she used the term Confederate troops. She, too, like Mr. Alabama, talked as though it was just basically an unfair fight. Ungentlemanly lopsided. I kept my mouth shut during these exchanges. Hard to believe. I know. I could tell that the wounds were still raw. There was no point in poking around in the wound with the facts. It was still fresh for these two; imagine after all these years. The two young men from Switzerland kept quiet, they looked away, embarrassed. The people from Oregon basically just ignored this part of the conversation and switched the topic by asking the fellows from Switzerland if they skied a lot in Switzerland.

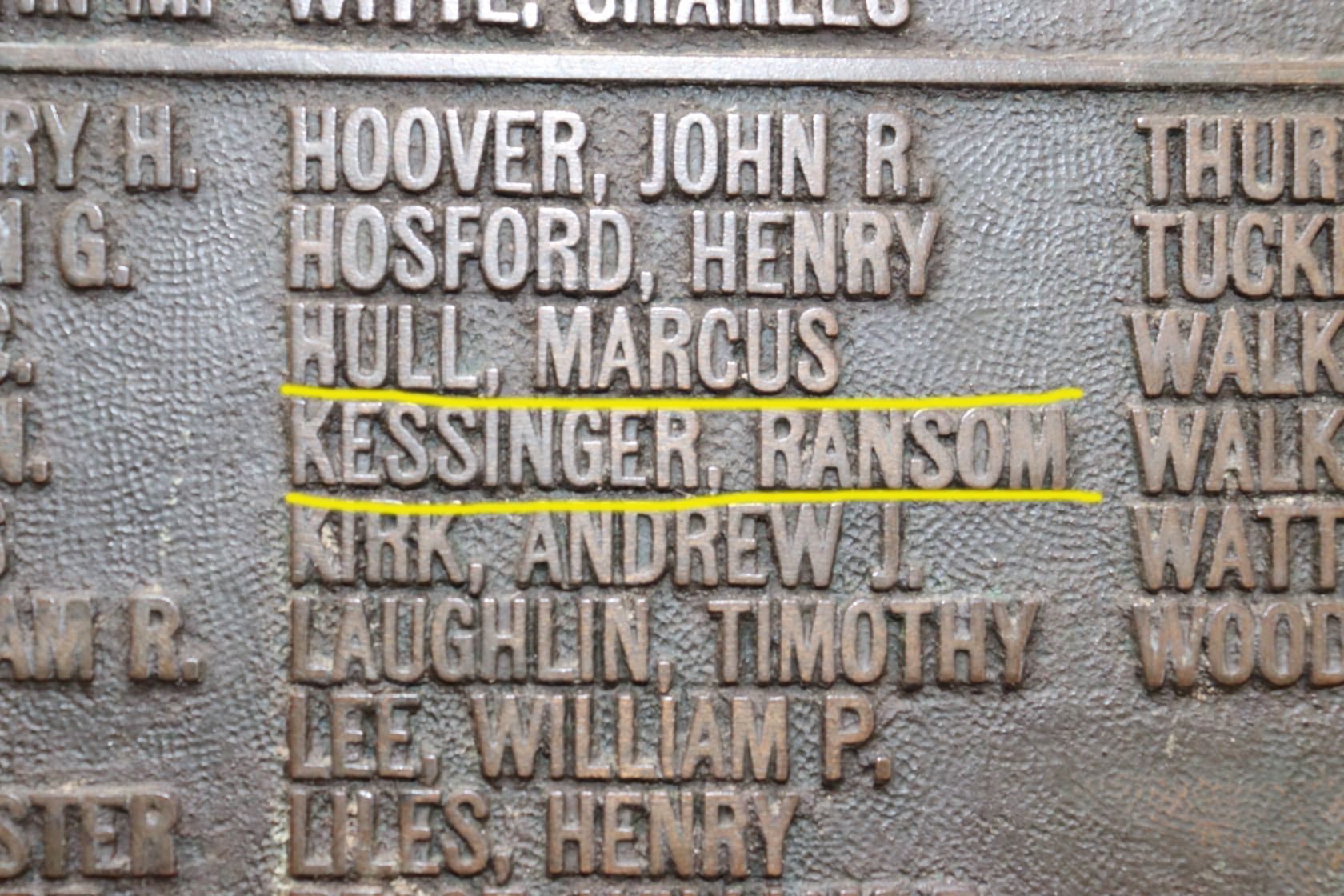

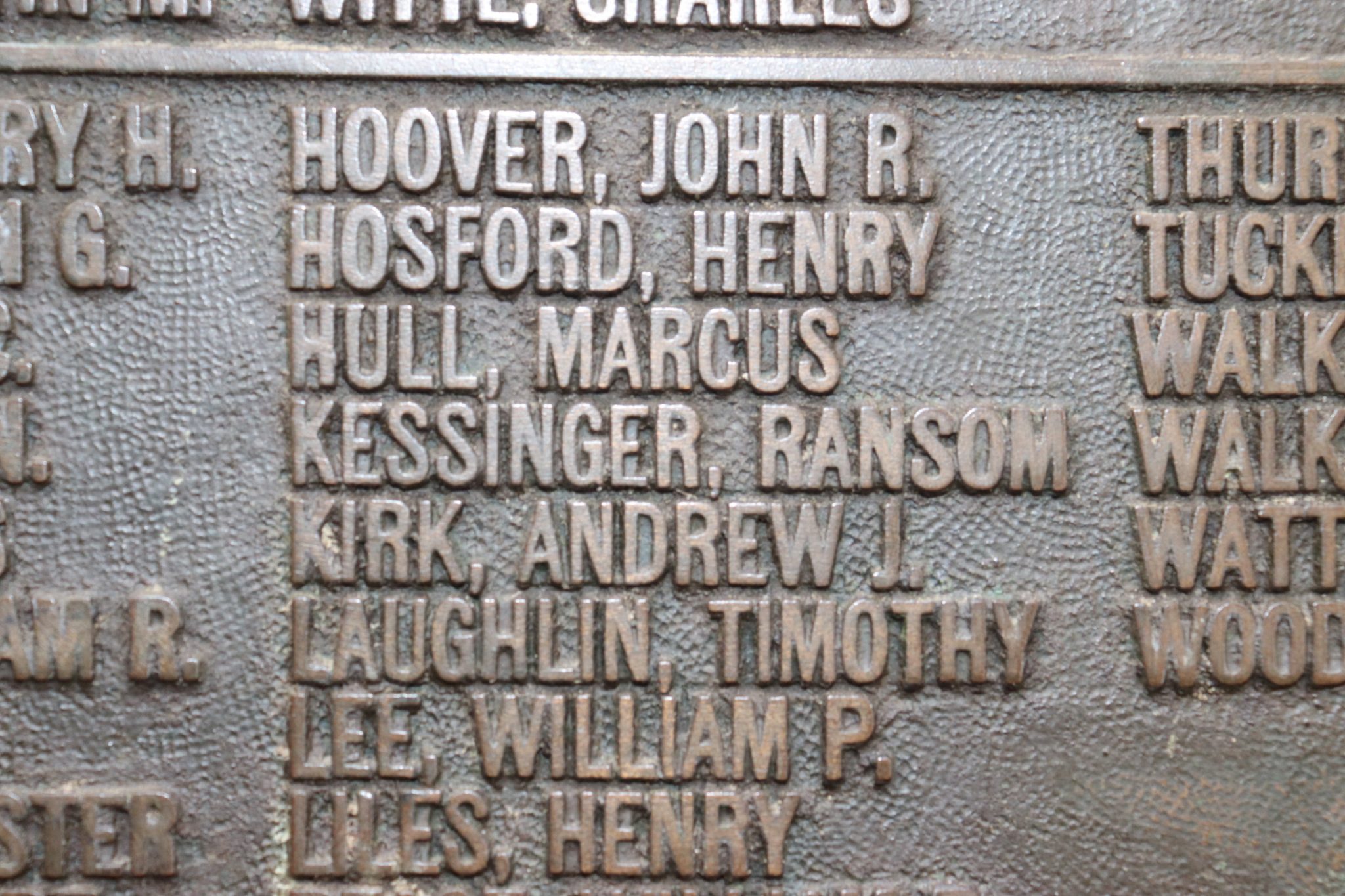

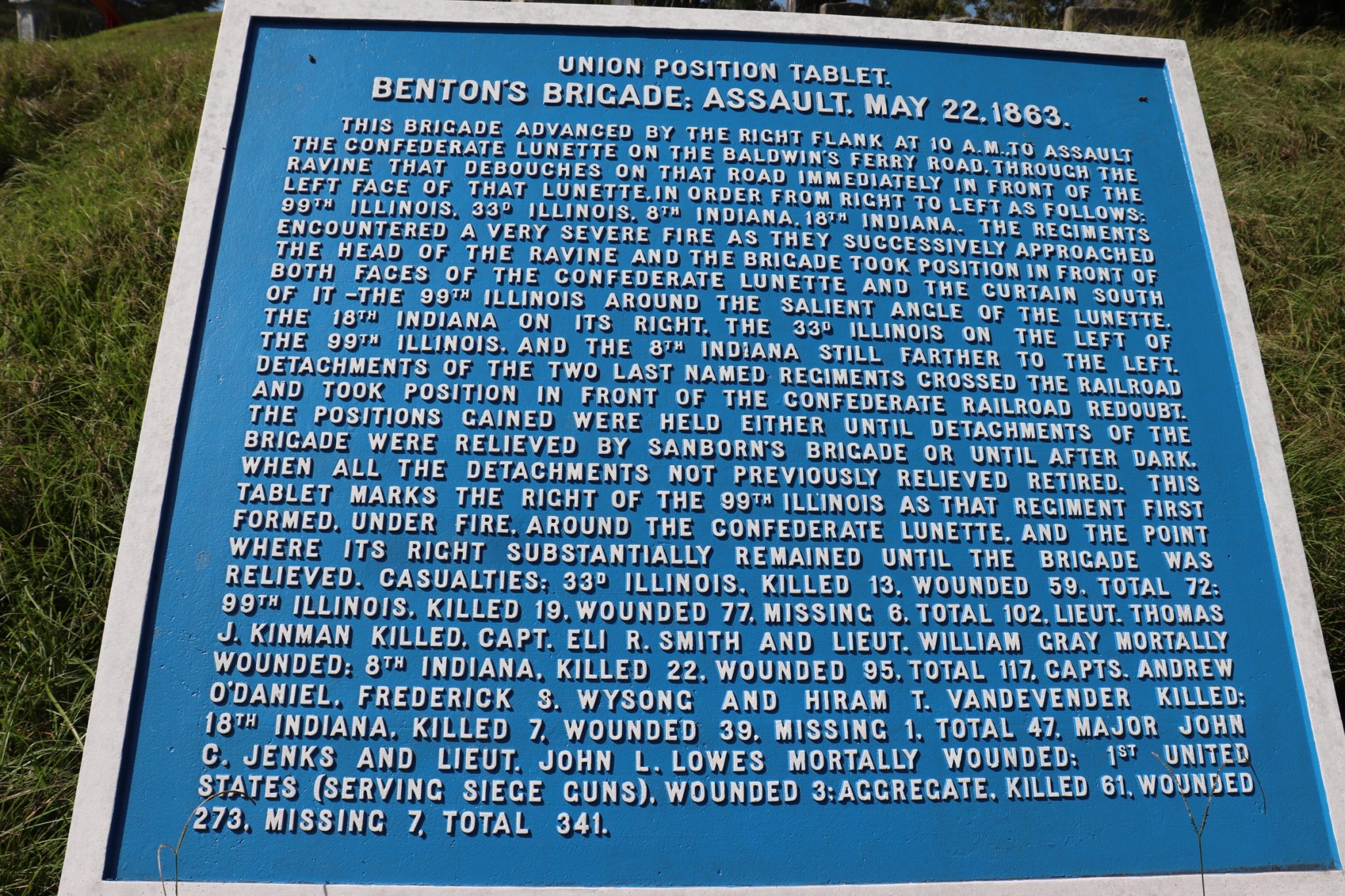

If one told me that two southern people, both clearly from good stock, would exhibit palpable emotions about the civil war at breakfast this morning, I would have been suspect. I would have believed it to be contrived emotion, manufactured for effect. Or, affect. That is, however, before I was moved by what I experienced while walking around nearly the entire Vicksburg battlefield yesterday. I shared my impressions last evening with cousin Jacob. There is an eerie presence of men, from both north and south, on that battlefield. Nothing spooky. Just eerie. Cousin Jacob agrees with me. He felt the eeriness of their presence when he visited the battle site, too. Vicksburg’s battle site commission is proud of the fact that it’s one of the best and most accurately marked battlefields in the world. Everywhere there are signs that indicate which unit manned what line on every hill; which artillery battery was atop of what crest on another hill. There are also signs that describe which units were part of a specific charge and how far it advanced. There are bronze reliefs dedicated to specific officers who were killed on the spot where the statue is erected. At one point along the walk there is an artillery battery, replete with civil war artillery pieces, a union outfit, facing across the hills from another artillery battery, a confederate unit. In the middle is a valley. That valley was a killing field. A great slaughter took place there. I have read essays about how the memory of the Civil War still lives in the south. With evidence of the great struggle in one’s back yard – how could it not? Yesterday, I sensed the chaos, the noise, and the smells. I chose not to share with the people at the breakfast table that my 4th great-grandfather, Ransom Kessinger, fought with Grant in the 99th Illinois. Somehow, it didn't seem polite.

Some of my earliest memories take place in the company of my grandmother O’Leary. She is the daughter of Occie Wagoner-Wheeler. Occie’s grandfather was Ransom Kessinger. For as far back as I can remember, my grandmother O’Leary used to drive me in her car every summer from Garden City, Michigan down to the farm in Peal, Illinois, just outside Pittsfield, Illinois, on the Illinois river. The Wheeler family settled in this area in the 1820s. The Kessinger family settling there probably in the 1840s or the 1850s. Every trip to the farm with my grandmother started with a family history tour. She took me to the several cemeteries that are important to our family, the Miller Cemetery comes to mind. We would get out and we would walk among the gravestones and she would point out our relatives and tell me a little bit about each one of them. We would stop at a small ad hoc family cemetery, now surrounded with a small chain link fence, that contains the graves of about four people. Maybe less. Two of those people, as I recall, were the young children of Ransom and Sarah Kessinger who died during the Civil War. Somehow, I recall hearing that it was a fire; Aunt Jeanne thinks it was disease that laid them low. But I'm not sure. I don't think Grandmother was sure either.

The tour of the area always included going by the original Wheeler homestead, now obscured by a forest. We also went by her parent’s small farmhouse. As we would drive by some dilapidated unoccupied home, crumpling among the fields of corn or beans, she would recite the name of the family that used to lived there, or point out the location of a one room school house, or the spot that a small grocery and sundries store used to occupy. So and So, “. . . used to live there,” or So and So, “. . . lived over there.” Two of the places that I used to love to go by were Dead Man’s Hill and the piece of Kessinger land on which a former slave used to live. Grandmother would not let me get out of the car to go and inspect the land where the black man lived. She would always say, “Too many snakes down there.” Then she would tell me the story of her father taking a garden spade and chopping up a copperhead snake one day that threatened her on their morning walk to the fields where the cows were kept.

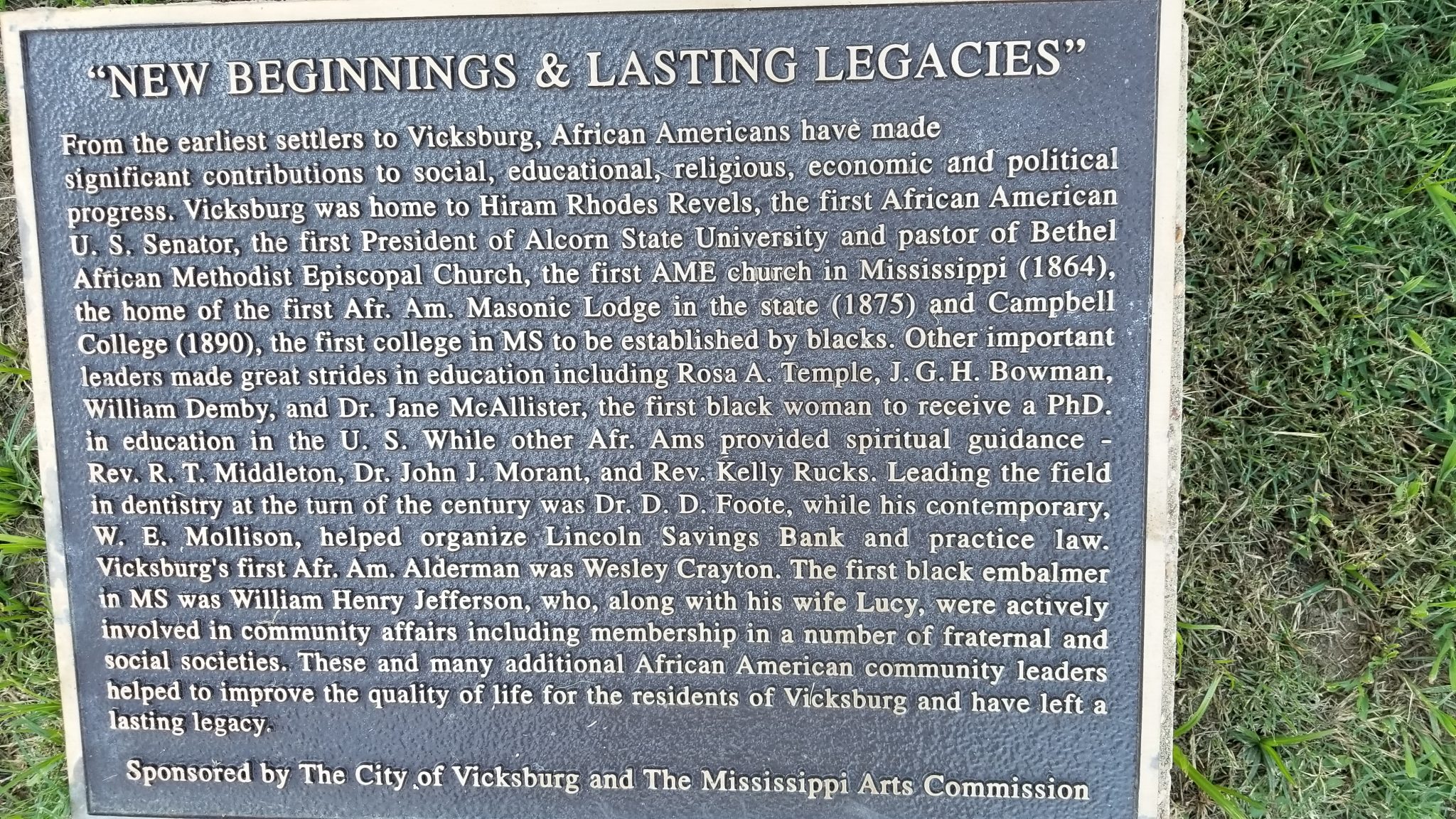

The story of Dead Man's Hill is prosaic. It was told in a matter-of-fact direct way. Apparently, a traveling salesman was messing around with somebody’s wife. The fella found out that he had been cuckolded by the itinerant salesman. As the story goes, he killed the interloper and the entire town stayed tight-lipped. That man got rough country justice. Justice, none the less. The story about the ex-slave is the story of race relations in America, both optimistic and apocryphal. Who knows how true. At the same time, I believe it, because I choose to. Ransom Kessinger befriended an ex-slave on the battlefield somewhere in the south and brought him home while he was on leave. The man stayed and worked on the Kessinger farm, greatly helping Sarah, while Ransom went back to his unit and resumed his part in the war. After the war’s end Ransom returned home and carved out a piece of his land for that black man to live on for the rest of his life. When that black man died Ransom Kessinger tried to have him buried at a local church cemetery. He was refused. The other church cemeteries refused him as well. They would not inter a black man into their so-called consecrated ground. Ransom Kessinger was outraged. Because he was such a successful farmer and businessman in the community, and very active in local politics, he imposed his will upon the town fathers and had that black man buried in the public cemetery. While he and his like minded compatriots were off fighting the war, the local southern Illinois politicians, so called ‘copperhead democrats,’ undermined the war effort. When Lincoln’s brigades returned home the tables were turned. Men like Ransom Kessinger called the tune in the years after the war in southern Illinois. I wish I could remember that black man’s name. I remember hearing it expressed as a derogatory appellation, a racist reference attached to a first name. Not worth remembering and certainly not worth repeating. It diminishes the otherwise good work of my great grandfather who I wish to believe would not approve.

Editors note: Aunt Jeanne says the man's name was Dan. The piece of land was called 'Old Dan's holler.' A 'holler' being a shallow depression in the land, like a valley.

The second to last stop on my grandmother's family history tour was always the grand two-story brick building that my great-grandfather Ransom Kessinger constructed as a home. He built it with the wealth that he created from the land. It was the only brick home in the area. I remember it was in great disrepair when I was a child. I also remember being greatly disappointed when I went to the farm as an adult and it had disappeared. Scraped from the land. All that is left of it now is part of the foundation. The last place we visited on the family history tour was always that little cemetery that contains the graves of those children.

At one time our family’s land holdings were comprised of about a thousand acres of prime Illinois black farmland. Slowly, the whole was split into smaller and smaller parcels as the sons of the fathers divided up the land. My grandmother's legacy is that she painstakingly put that thousand acres of land back together over the course of her life. Legacy is fleeting, however. Her heirs will sell the land. Who can blame them? Nobody in the family wants to farm. Grandmother O'Leary didn't farm either. She used tenant farmers – and did not trust them a lick.

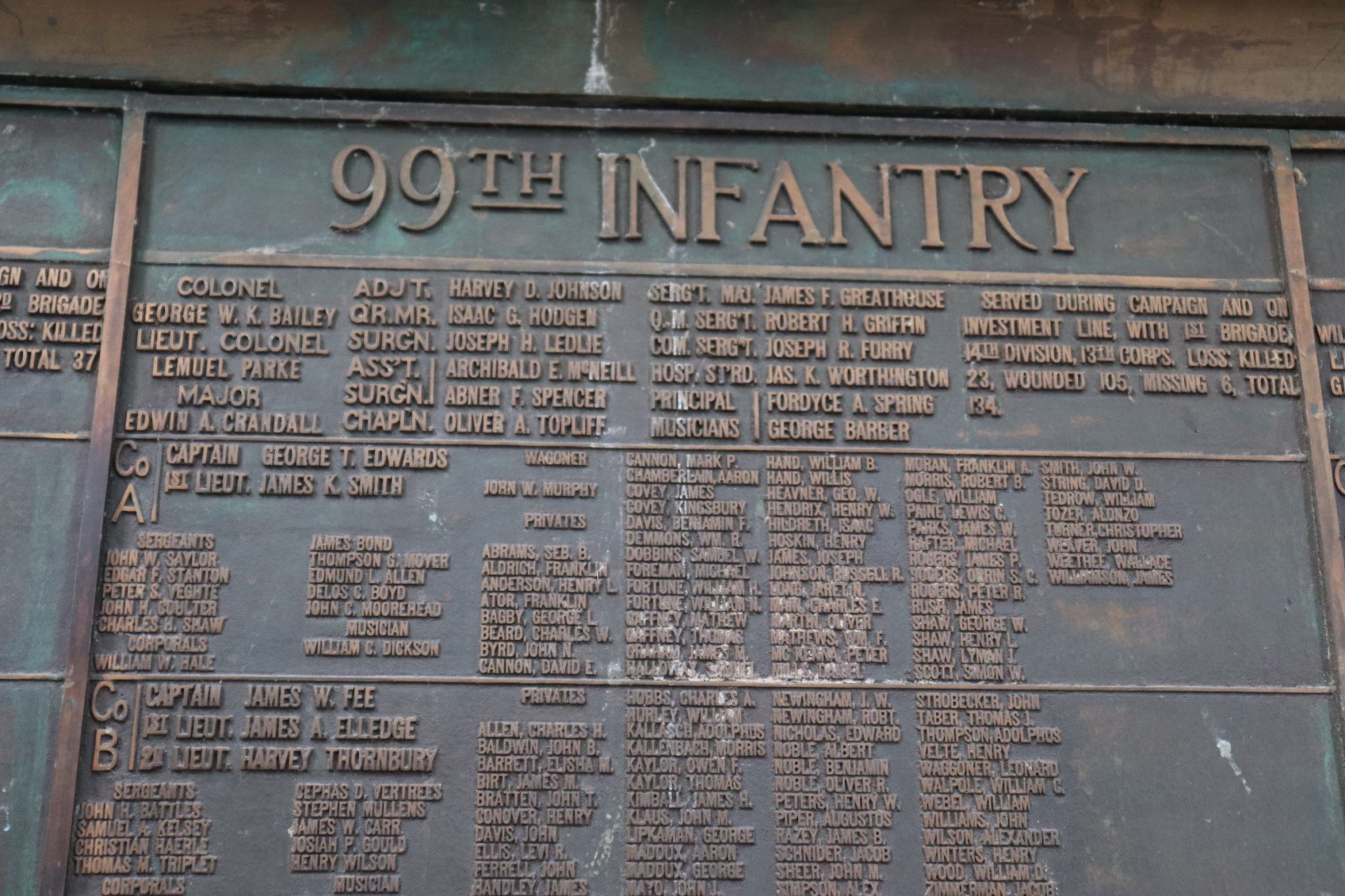

In 1862, Ransom Kessinger mustered into the Union Army and into the ranks as a private in the 99th Illinois in Pittsfield, Illinois. He endured the privation of the war through to its conclusion in 1865. He mustered out in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It's likely he took ship and sailed all the way up the Mississippi, to where it converges with the Illinois river, and he disembarked from it on the banks of the Illinois close to his hometown of Pearl, Illinois. But before he took that ship ride home, he and his comrades walked for over 5,900 miles and fought in the most important battle of the civil war, the battle that opened the south to the armies of the north. He participated in the second assault on the garrison at Vicksburg under Grant. Immediately, after the capitulation of the Confederate troops that defended Vicksburg, he marched under Sherman to fight in the battle of Jackson, Mississippi. From there his unit went West to accept the surrender, by treaty, of several Native American tribes. After fighting a smaller action in Texas, he returned to Louisiana where he ended his uniformed service to his country.

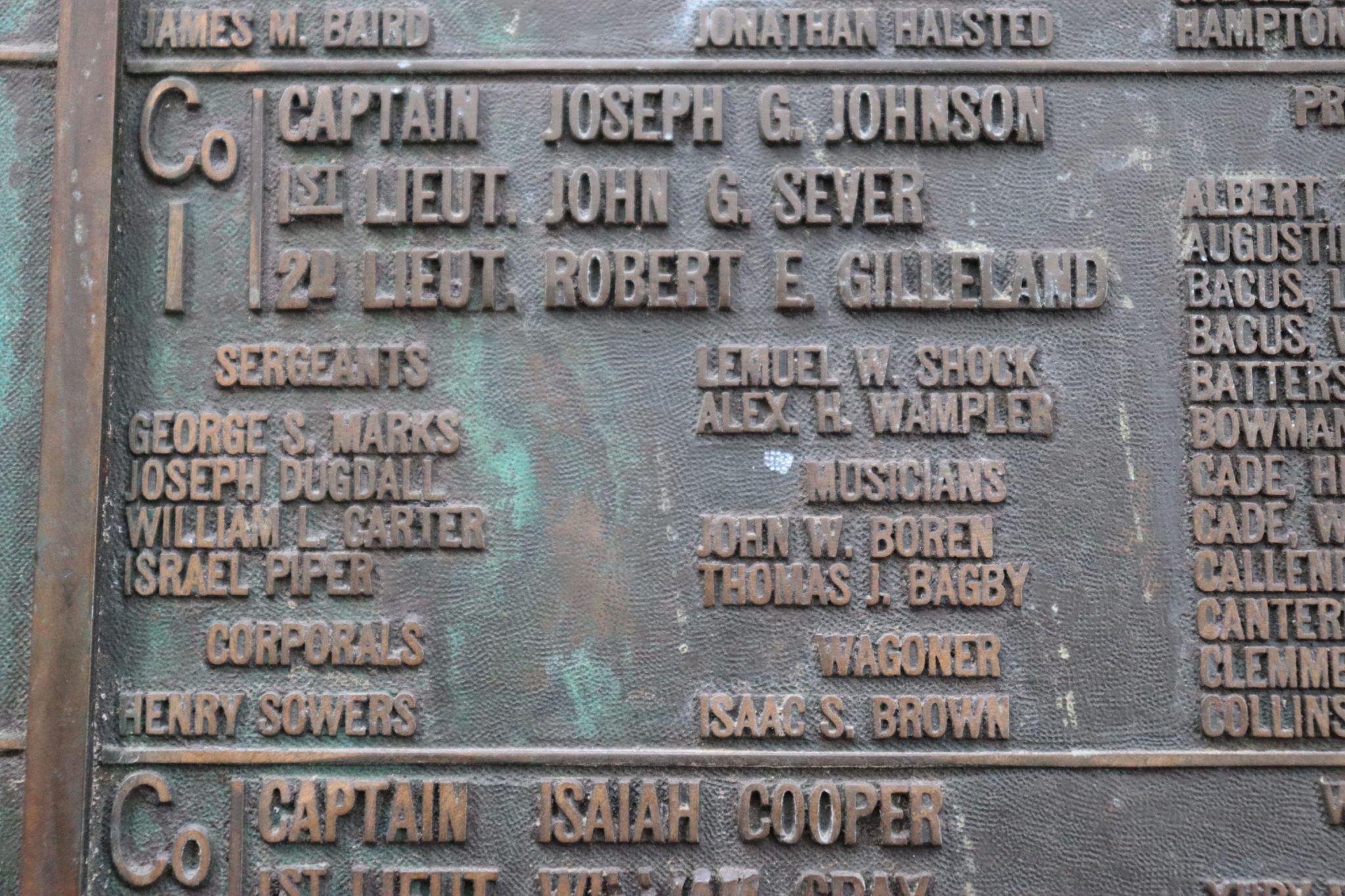

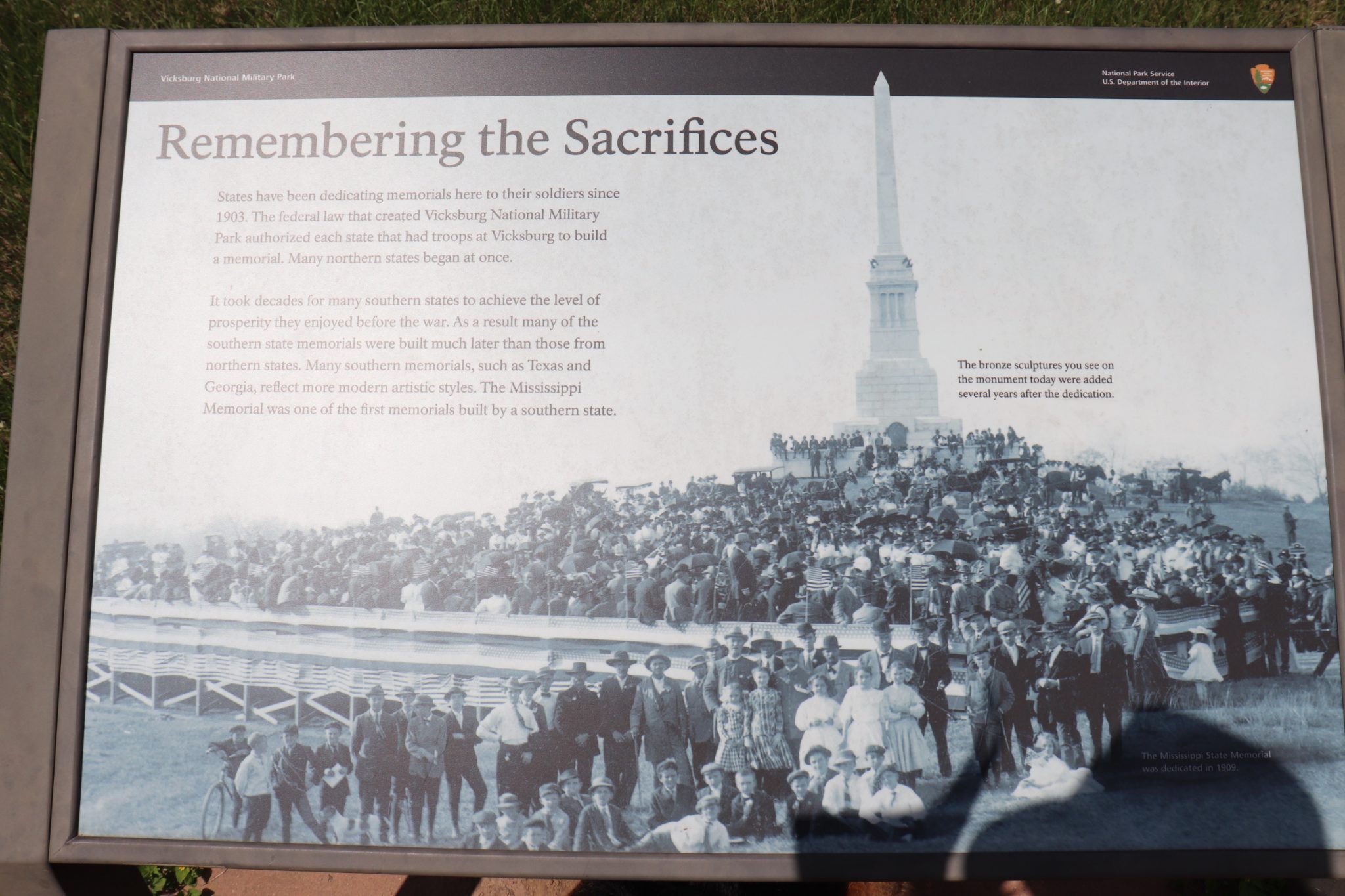

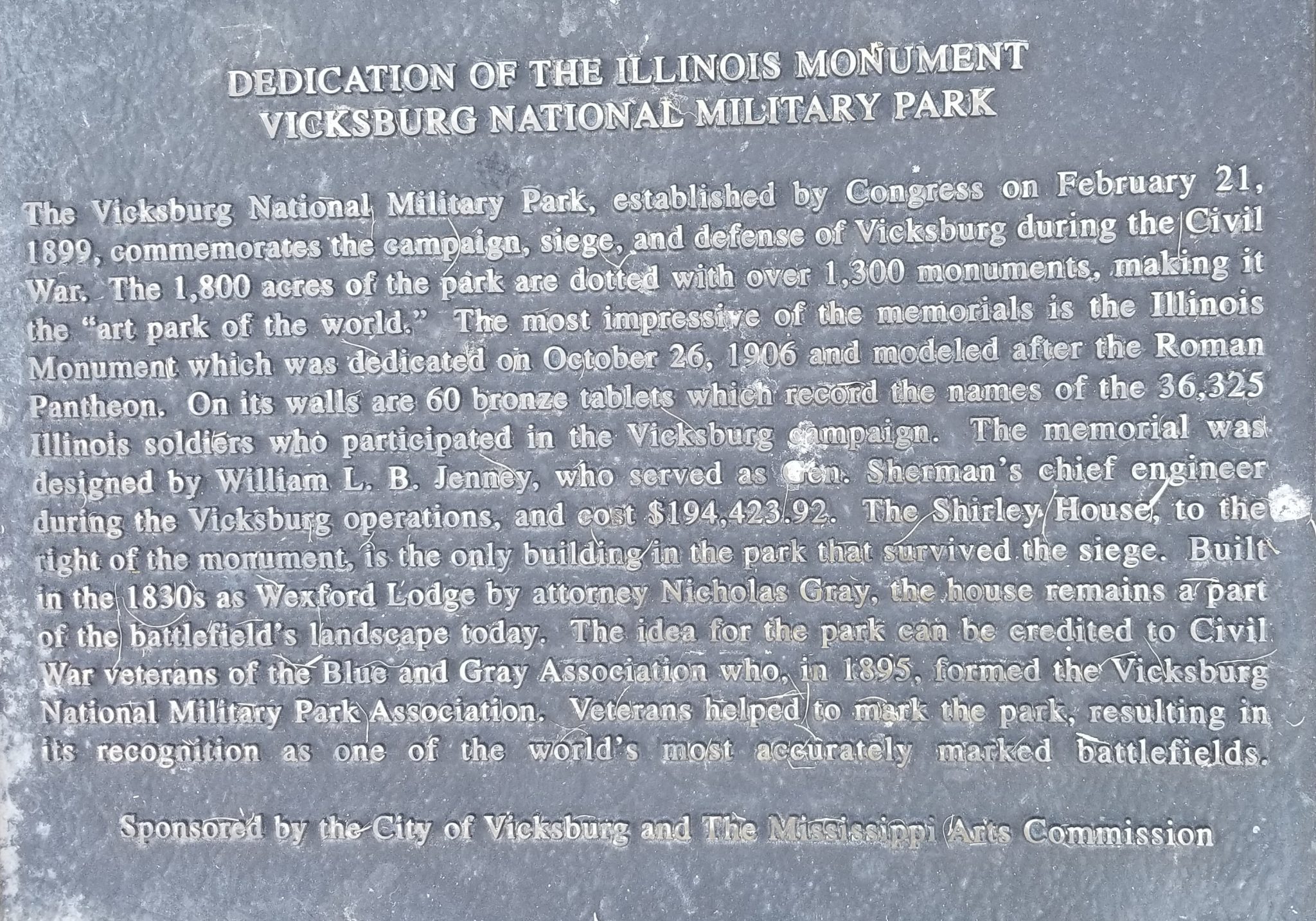

Of the 70,000 Union Soldiers that besieged Vicksburg, 37,000 were in units that mustered in the state of Illinois. The land of Lincoln provided, by far, the largest contingent of northern troops to fight in Vicksburg. The Illinois Monument building dedicated in the first decade of the 20th century is the grandest of any of the monuments erected on the Vicksburg battlefield site. The name of every resident of the state of Illinois who fought in the battle is inscribed on bronze plaques that ring the inside of the monument. A few years back I went with my friend Bob Bennett to the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington DC. He was on a mission to find the name of a young man he grew up with who died in the Vietnam war. His name is inscribed on that black shiny wall that emerges from the ground off the mall. Emotions got the better of Bob Bennett that day. Those emotions are contagious. I felt it, too; and I didn't even know that young man. I felt similar emotions yesterday when I found Ransom Kessinger’s name inscribed on those bronze plaques that encircle the inside of the Illinois War Memorial.

As noted, Teddie and I walked a good portion of the battlefield. Most of it while we searched for the various plaques that commemorate the deeds of the 99th Illinois. They were not easy to find. Some of the plaques are not on the battlefield site at all. They reside across Clay Street. One that I located was placed in a small gully, down a hillside, off the shoulder of the road. It’s where the sharpshooters for the 99th set up a firing line. I never did find three of the plaques that I tried to locate. I had to download their images from the internet. All three are located near, or in, an old Jewish cemetery. There were plenty of signs declaring the cemetery as private property. I felt uncomfortable walking among the gravestones looking for the plaques. A soon as I stepped inside the cemetery I thought better of it and Teddie and I returned to the battlefield.

The temperature was above 90° and certainly in the 90’s regarding humidity. We walked about four miles yesterday and Teddie was just about done in by the heat and the humidity. This is October. It is hard to imagine what the conditions were like here in the summer of 1863. Day-after-day and night-after-night those fighting men, on both sides, endured the fear and hot humid Mississippi weather. Teddie and I found relief from the heat inside Steele Cottage, an antebellum home built in 1829, where she and I spent the night. The cottage is owned by the family that owns the mansion where breakfast was held this morning. Yesterday, I left Teddie in the air-conditioned room and went out for an early dinner at a local restaurant. When I came back she and I took a walk down to the Mississippi River. The local Vicksburg Arts and Historical Associations sponsored the painting of about thirty mural panels erected along the Waterfront. I think that is a great way to teach history. Of course, none of those panels showed the slaves loading the ships with cotton that sailed North to go to the merchants who continued to buy cotton throughout the entire war. Something Grant put a stop to. None of those panels depicted the slave markets, either. In fairness, none of those panels showed the graphic privation and starvation that the army of the South, and the the residents of Vicksburg, endured for the forty-seven days they were under siege.

Teddie and I walked down to the water and I took a vial out of my pocket. I have carried that medicine vial containing the cremated remains of Alice King since it was entrusted to me by Wayne King on the day of Alice's memorial service, back in late July. Some of Alice is in a fast-moving stream in Montana. Some is in a river in Idaho. Yesterday, the sun was low in the sky and shining off the Mississippi River. I noticed a flag at half-staff, it seemed appropriate. I bent over, and I poured the remaining contents of that vial into the Mississippi River. There were two families of African Americans sitting in cars, talking to each other through opened windows, parked by the river. I could see that they watched me as I poured the contents into the water. I stood up, put the cap back on the vial, walked over to a trash receptacle, kissed that vial and deposited it in the container. With great sadness and contemplation, I walked back up the boat ramp to the street with Teddie.

Tonight, we will be in Pensacola Florida. My daughter, Dawn, tells me that I should eat at The Fish House, Peg Leg Pete's or Joe Patti's restaurant. I want some grouper and she tells me that they source it fresh daily.