January 29, 2024

"Whoever chafes at the conditions dealt by fate is unskilled in the art of life, whoever bears with them nobly and makes wise use of the results is a man who deserves to be considered good." Epictetus, Discourses and selected writings.

Epictetus was a slave. In fact, his name literally means slave. He famously bore the pain of an abusive master who broke his leg, which never healed properly, causing him to walk with a limp for the rest of his life. I thought of Epictetus yesterday when we visited the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Georgia. The museum describes itself as focusing on Southern art; it does so in the main. Not all the art, photography, sculpture and paintings are from the hands of Southern artists, but The South is their theme, even if the artist is foreign to the South.

One painting stuck with me long after we left. I continue to reflect on it. Yet, I almost missed it. Jill pointed it out to me because she was moved by the story attributed to the scene painted in oils. Once I read the story the painting came to life and Epictetus came to mind.

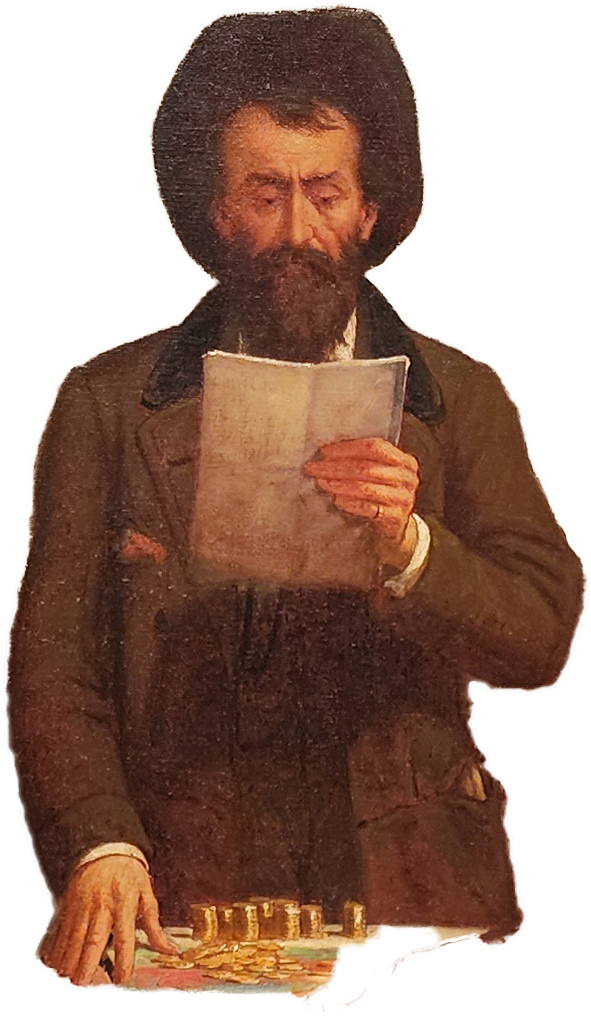

The scene takes place in a 19ᵗʰ century drawing room. Three men are present. Two are standing and one man is seated in a fine leather office chair with the claw legs on casters so that he can easily roll himself away from the table at will. There are only two chairs, the seated man's chair and a high back inlaid wooden chair that one of the men is standing in front of, having just pushed it back so that he can stand up. He leans on the table with his right hand, slightly supporting his weight, as he reviews a document he holds in his left hand. In front of him are stacks of gold coins laying on the richly colored and embroidered tablecloth. His hat is tipped way back on his head revealing his forehead as he reads the document. His waistcoat is buttoned; his full beard hides his expression as he closes the deal. On the table, not far from the coins is a silver tray. On which is a decanter of brandy and two empty crystal glasses. Also on the table is a bronze inkwell with a document stamp resting on it to affix to the contract when the negotiation is complete.

The chattel is the third man. Our Epictetus. The slave. He stands there stoically looking away from the scene with an expression of resignation on his biracial and light-skinned brown face. His features resemble the seated man. He is wearing a clean linen shirt made from flax and a pair of trousers, dark with no holes or signs of wear. He has his left hand resting on his hip and in his right hand he holds a straw hat loosely by the brim. He is barefooted and he does not wear a belt. He appears to be healthy, and one can assume that his life has been spent serving his master from inside the plantation house. His master is his father and today he is being sold.

And yet as stark as this scene is, his father, the master of all he surveys, is the most striking of all in this painting. The old man slouches in his chair, wearing a richly made gray robe with scarlet red cuffs and collar loosely tied at the waist with red and black cord. His right-hand rests on the table by a stack of paper, the ownership documents of his slave. His son.

His long hair is parted and uncombed and he sports a great salt and pepper beard that rests on his chest obscuring the red collar of his robe. He wears fine leather slippers on his feet. Clearly a man of great wealth. He stares right at me with his left eye, eyebrow arched, his other eye barely seen hidden in the shadow of his profile. He is staring at you, too. The only subject of the painting to offer eye contact. He is steps out of character for just a moment to engage the audience in a dialogue just like we are watching a stage performance where the action freezes and the protagonist speaks directly to you. To me, too.

I hear him saying, "Well, what do you think about this?" He is unabashed. "You would do the same. Wouldn't you?"

I imagine that his wife is fed up with the presence of his living sin, his son, working and living under the same roof as she and her children. Sick of seeing him, Epictetus the slave, passing her in the corridors of her castle. Reminding her every day that he sprouts from her husband's loins. Unbearable.

The old man concludes, “Happy wife; happy life."

Then he affixes his seal and pours a brandy for himself and the slave’s new owner. Together they toast the conclusion of this grotesque transaction. This abomination. This Faustian bargain.